*This is the fourth part in our series, “Onggi, traditional earthenware vessel in Korea.”

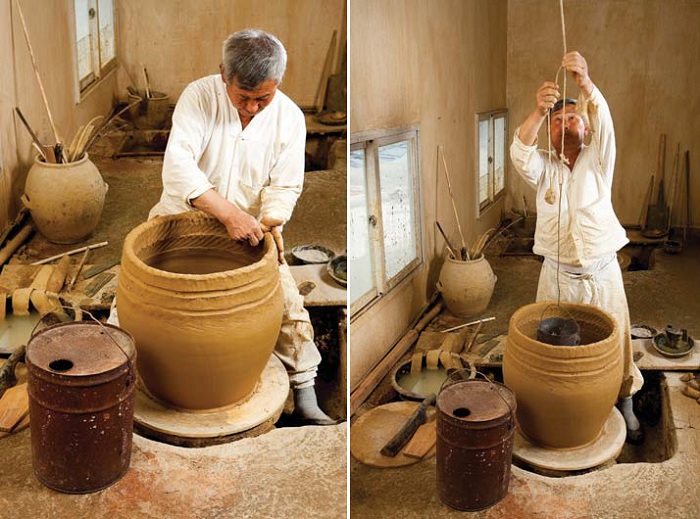

Shaping the Pottery

An expert potter, a daejang in Korean, is one who can shape the raw clay.

A master potter makes the bottom of the urn first. This process is called the mulrekan in Korean. Afterward, he shapes the main body using a technique called geureutssatgi. He then shapes the mouth of the urn.

How to shape traditional pottery urns

Shaping the main body of the urn, the geureutssatgi process, can be started after the bottom of the urn is completed. There are two shaping techniques, depending on the size of the final product.

The first one is shaped from the base on up, a technique done by hand for smaller pottery artifacts. The second one is uses suitable tools and is generally used for larger urns. This tarimjil process for larger urns is done by smoothly shaping the surface of the pottery using a variety of tools, depending on the size and shape of the final product. This process, in turn, is broken up into three methods.

The first has the craftsman piling layer upon layer of rope-like clay strips, the tessatgi process. The second has the craftsman spiral one long rope-like clay strip upon itself, the seorigi process. Finally, the chetbakui tarim process, has the craftsman build walls, layer by layer, with long slaps of clay.

When shaping large urns, a wood charcoal-burning brazier is placed inside the half-finished pottery, helping to dry and shape the urn and at the same time prevent it from collapsing from the weight of the wet clay.

After the body of the urn is made, the rim around the mouth is shaped and finished with a touch of decoration above and below the body center. When the surface decoration is finished, the raw earthenware can be cut off of the potter's wheel to be dried.

Shaping the Bottom

Before the master potter sits down at his wheel, he spreads white clay powder over the surface of the potter's wheel to prevent the clay from sticking. The clay is padded down to the appropriate thickness for the bottom of the urn and, as the wheel spins, the craftsman uses a wooden knife to cut out the shape of the urn's underside.

*This series of article has been made possible through the cooperation of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. (Source: Intangible Cultural Heritage of Korea)

Shaping the Pottery

An expert potter, a daejang in Korean, is one who can shape the raw clay.

A master potter makes the bottom of the urn first. This process is called the mulrekan in Korean. Afterward, he shapes the main body using a technique called geureutssatgi. He then shapes the mouth of the urn.

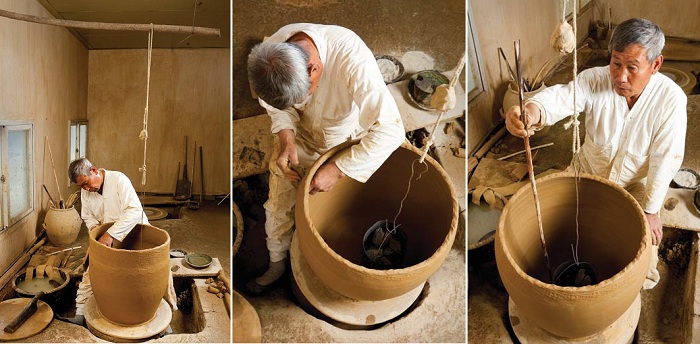

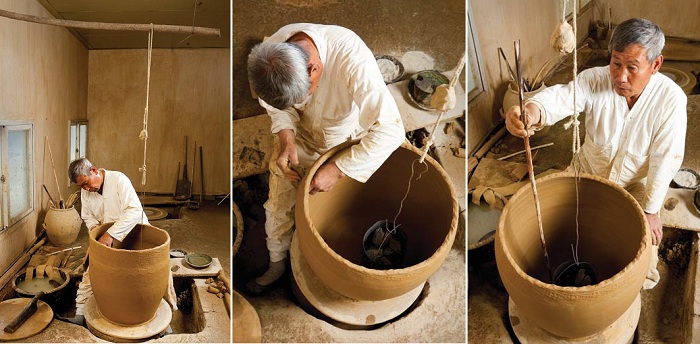

(Top,

left) The base of the urn is built up by hand; (Top, right) The sides

of the urn are built up by placing layer upon layer of long, round clay

strips; (Bottom, left) The urn is shaped with a spiral layer-upon-layer

construction of a long, cylindrical clay strip; (Bottom, right) The

sides are finished with a long, thin slab of shaped clay.

How to shape traditional pottery urns

Shaping the main body of the urn, the geureutssatgi process, can be started after the bottom of the urn is completed. There are two shaping techniques, depending on the size of the final product.

The first one is shaped from the base on up, a technique done by hand for smaller pottery artifacts. The second one is uses suitable tools and is generally used for larger urns. This tarimjil process for larger urns is done by smoothly shaping the surface of the pottery using a variety of tools, depending on the size and shape of the final product. This process, in turn, is broken up into three methods.

The first has the craftsman piling layer upon layer of rope-like clay strips, the tessatgi process. The second has the craftsman spiral one long rope-like clay strip upon itself, the seorigi process. Finally, the chetbakui tarim process, has the craftsman build walls, layer by layer, with long slaps of clay.

When shaping large urns, a wood charcoal-burning brazier is placed inside the half-finished pottery, helping to dry and shape the urn and at the same time prevent it from collapsing from the weight of the wet clay.

After the body of the urn is made, the rim around the mouth is shaped and finished with a touch of decoration above and below the body center. When the surface decoration is finished, the raw earthenware can be cut off of the potter's wheel to be dried.

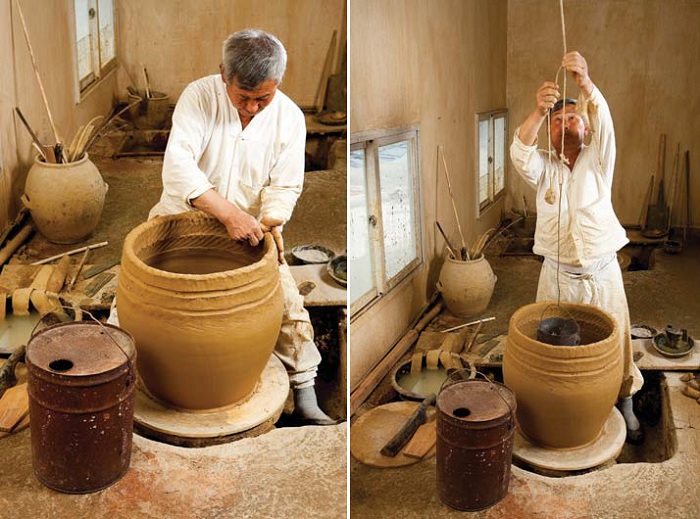

(1)

The bottom of the urn is begun with a simply lump of clay. (2) Spread

white clay powder over the surface of the potter's wheel to prevent the

clay from sticking. (3) Shape the bottom of the urn by pounding and

spreading the lump of clay with a roller pin-like tool.

Shaping the Bottom

Before the master potter sits down at his wheel, he spreads white clay powder over the surface of the potter's wheel to prevent the clay from sticking. The clay is padded down to the appropriate thickness for the bottom of the urn and, as the wheel spins, the craftsman uses a wooden knife to cut out the shape of the urn's underside.

(4)

The bottom of the urn is shaped by pounding and spreading the clay with

a large roller pin-like tool. (5) The bottom of the urn is measured

precisely. (6) The excess clay is cut away.(7) In order to link the

bottom with the sides, it is slightly broadened with a mallet.

(8)

The artisan shapes the pottery from the base, forming each layer by

hand. (9) It is essential to firmly connect the bottom of the urn with

the first layer. (10) Each subsequent layer of clay is carefully placed

atop the lower layers. (11) The artisan uses his hands to shape the

sides of the urn.

(12)

The craftsman continues with the upper layers of the side.(13) The

potter can use both hands and tools. The left hand, inside the urn,

holds the sides in place as the right hand, outside the urn, taps the

sides to make the thickness even. (14) Smooth the surface of the sides

using a geungae. (15) Trim the inside of the urn.

(16)

The pottery is shaped upward by hand. (17) The craftsman can use both

hands and tools at the same time. The left hand, on the inside, holds

the sides steady while the right hand, on the outside, taps the sides to

make them even. (18) The potter carefully measures the circumference of

the urn, making sure it's even. (19) Each later is securely connected

to the lower layers using the fingers.

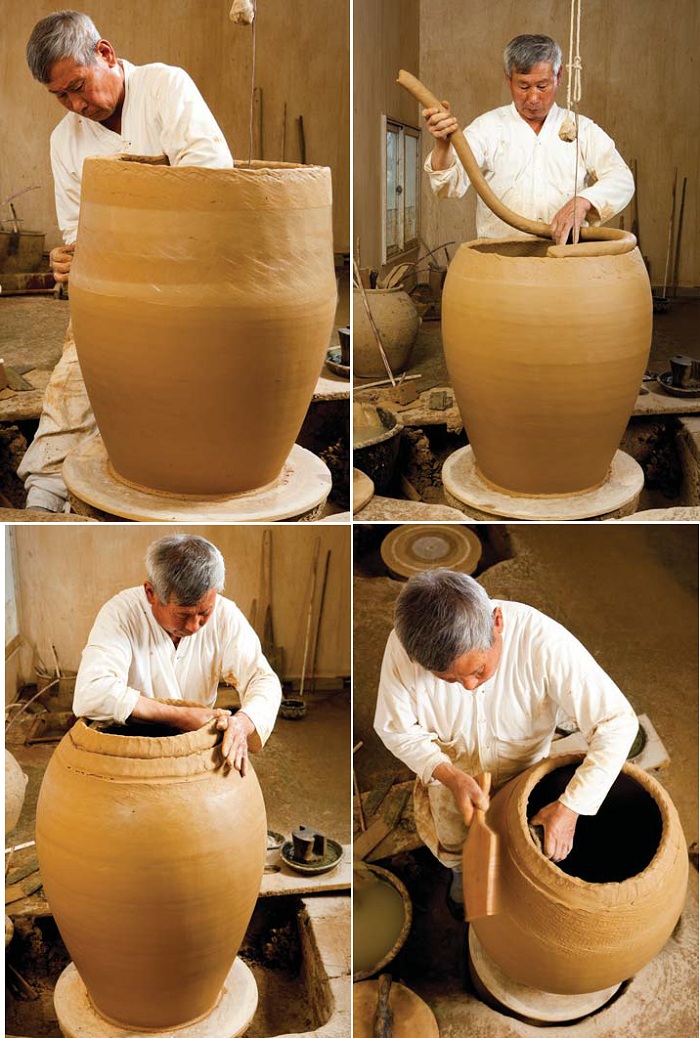

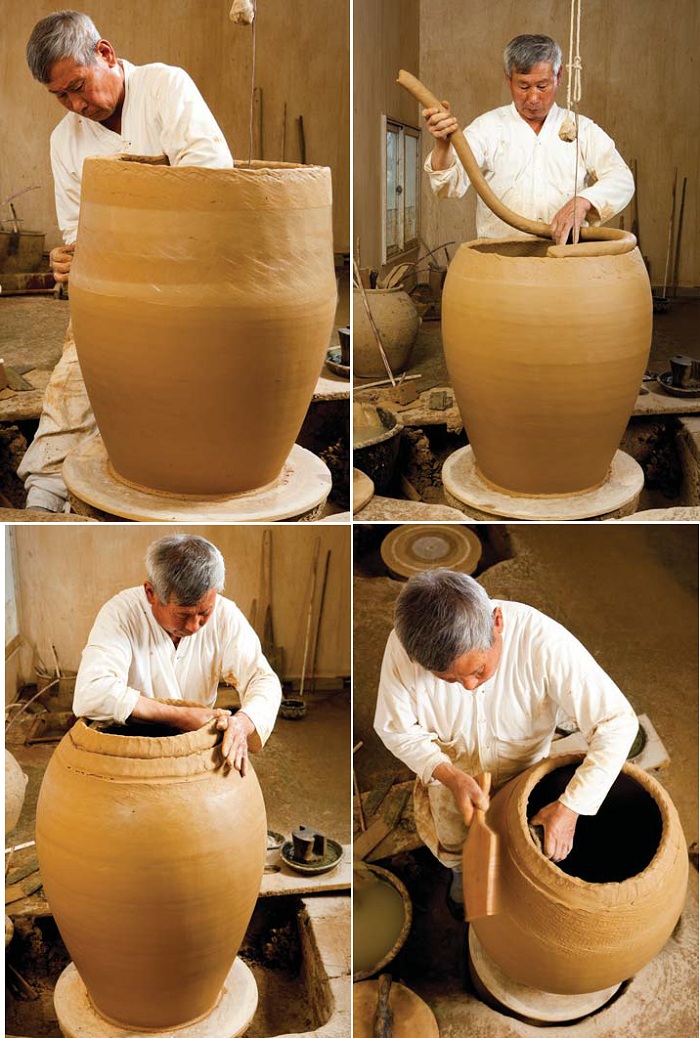

(20)

As the layers of the side are put in place, the craftsman uses his

index finger to "pinch" the two layers together. (21) The outside of the

urn is also sealed using the fingers.

(22)

The pottery is shaped by hand from the base and up the sides. (23) When

shaping larger urns, the potter places a brazier of wood charcoal

inside to help dry the clay and to help prevent the walls from

collapsing as he continues to work.

(24)

Hanging a burning brazier inside the unfinished urn helps to dry the

clay as the artisan continues to shape the sides. (25) The craftsman

hangs a charcoal-burning brazier inside the unfinished urn as he trims

the sides with a geungae, a tool used for trimming. (26) The potter

measures the height of the urn with a graduated length of wood.

(27)

The artisan trims the sides of the urn with a geungae. (28) A length of

rope helps the potter to shape the sides of the larger urns. (29) The

final layers of clay are laid for the upper edge of the sides. (30) The

craftsman uses a tool in each hand to finalize the proper shape of the

sides.

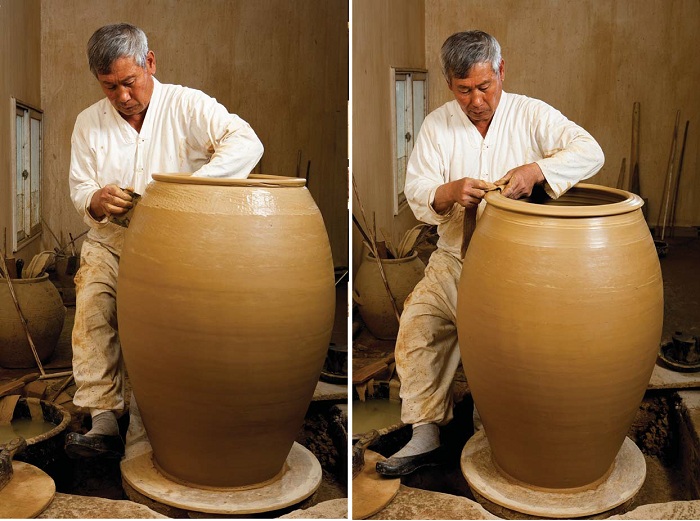

(31)

Excess clay is cut away along the lip. (32) A cloth or a strip of

leather is used to shape the final opening. (33) The final lip is shaped

with a strip of cloth or leather. (34) The potter measures the width of

the opening, making sure the urn is properly balanced.

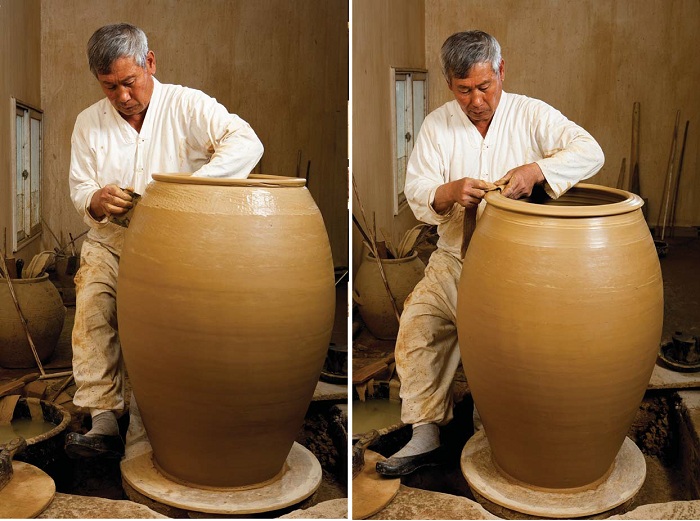

(35)

The artisan uses a geungae to trim to top of the almost-finished urn.

(36) The craftsman uses a strip of cloth or leather to smooth the upper

lip of the urn.

(37)

The potter makes an intaglio, or indented, pattern along the inner

sides of the urn. (38) A square of leather is used to make an indented

pattern, an intaglio, along the outside of the urn. (39) Simple indented

patterns can be made by hand along the outside of the urn. The final

work of pottery must be cut from the potter's wheel before being placed

in the kiln.

40. The raw urn is finally finished.

*This series of article has been made possible through the cooperation of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. (Source: Intangible Cultural Heritage of Korea)

Comments

Post a Comment